Organizations must innovate in the globalized business environment to stay competitive and profitable or maintain market presence.

Yet innovating is far from straightforward. It demands significant alterations in the organizational culture, often met with various obstacles during the change process.

Resistance to change is a common phenomenon, occurring when individuals become so entrenched in their routines that they struggle to adapt when faced with new circumstances.

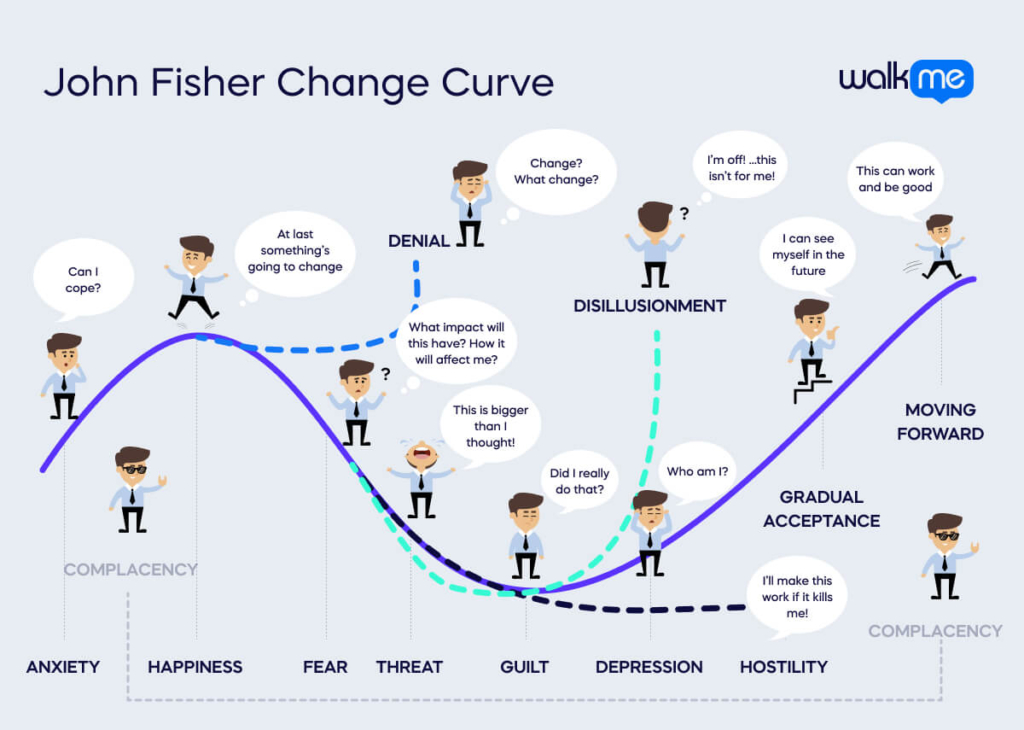

The John Fisher Change Curve illustrates that adaptation to change is a unique journey for everyone. Not all individuals will experience every transition stage; some may get stuck in denial or disillusionment, others might withdraw during challenging phases, and some adapt more smoothly and quickly.

In this guide, we will go through the John Fisher Change Curve, its origins, the model’s different stages, what it means for change management and a step-by-step guide to implementing it within your company.

What is the John Fisher Change Curve?

The John Fisher Change Curve explores how people react to organizational changes. Fisher outlines eight main stages of personal adjustment during workplace transitions, from ‘anxiety’ to ‘moving forward.’ It’s important to note that these stages vary in length and impact for individuals, even within the same organization.

Additionally, Fisher highlights three specific ‘points’ where individuals might be stalled in the transition process.

These points include ‘denial’ or ‘hostility’ towards the change, ‘disillusionment’—which could lead to deciding to leave the organization, and ‘complacency,’ which may be present at any stage of the process and could be considered as a final ninth stage.

These phases indicate a journey through varying levels of self-esteem as one navigates through change.

Origin of the John Fisher Change Curve

The John Fisher Change Curve model was built upon the foundational psychological research initiated by Elisabeth Kübler-Ross in 1973, focusing on themes of death, loss, and grief.

According to his coaching and counseling development website, Fisher introduced his model to the public in the paper ‘Fisher J M, 2000, Creating the Future?’. This paper was presented at the 1999 International Congress on Personal Construct Psychology in Berlin.

What are the different stages of the John Fisher Change Curve?

Understanding the phases of the John Fisher Change Curve is crucial for individuals and organizations alike to navigate the complexities of change effectively.

Recognizing the emotional responses at each stage allows for targeted interventions to mitigate the negative impacts of transition, ultimately leading to a more resilient and agile workforce.

Through the Change Curve model, Fisher states that each individual passes through a series of states or transitions and stumbling blocks, which are:

Phase 1: Anxiety

The journey through change begins with anxiety, a natural response to the uncertainty of the future. This phase is characterized by a pervasive fear of the unknown, where individuals struggle to envision what lies ahead. The inability to predict outcomes triggers a sense of apprehension, making navigating the initial stages of transition challenging.

Phase 2: Happiness

Following the anxiety phase, individuals enter a state of happiness fueled by the prospect of positive change. This phase is marked by hopeful anticipation and, often, unrealistic expectations about the future.

It embodies a dreamlike optimism where the desire for improvement overshadows the reality of the situation.

The happiness phase is a psychological relief, temporarily escaping the status quo and igniting excitement for potential advancements. However, this phase requires careful management to match expectations with reality, ensuring individuals remain grounded in achievable goals.

Phase 3: Fear

As the euphoria of the happiness phase diminishes, fear takes hold. This phase is characterized by the emergence of doubts and minor behavioral changes, signaling a growing awareness of the need for personal adaptation.

Fear stems from the realization that change is imminent and unavoidable, leading to apprehension about one’s ability to adjust to new circumstances.

Phase 4: Threat

The threat phase represents a critical point in the transition curve, where individuals come face-to-face with the implications of change on their core identity.

This phase is a profound psychological moment, akin to a personal revelation, where previous beliefs and choices are questioned. The shock of discovering that one’s self-perception may no longer align with reality can destabilize, prompting a deep existential crisis.

Phase 5: Guilt

Guilt surfaces as individuals reflect on their past actions and recognize mistakes. This introspective phase involves a painful acknowledgment of one’s role in contributing to less-than-ideal outcomes.

The ensuing guilt can lead to further emotional turmoil, potentially resulting in depression or disillusionment, depending on the individual’s coping mechanisms.

Phase 6: Depression

Depression during a transition signifies a profound realization that our past behaviors, actions, and beliefs clash significantly with our self-identity. This realization creates a sense of not being the person we thought we were, leading to confusion, lack of motivation, and a disconnection from our core self.

As individuals grapple with these insights, they face uncertainty about their future and struggle to see how they fit into a new or changing environment. This stage is marked by an identity crisis, with individuals feeling lost without a clear sense of direction or understanding of moving forward.

Phase 7: Gradual acceptance

The phase of gradual acceptance emerges as individuals start making sense of their surroundings and place within the changes occurring. This period is characterized by the beginnings of self-validation and the recognition that their path is correct.

Individuals start to regain control over the changes, understanding the situation’s ‘what’ and ‘why’ and beginning to see successes in their interactions. This stage boosts self-confidence as people start feeling aligned with their actions and beliefs, indicative of a better fit within their core role structure.

Phase 8: Moving forward

Moving forward is a phase of regaining control and making positive strides. Individuals rediscover their sense of self and feel confident in their actions and decisions, aligning with their convictions and beliefs. This stage involves actively and effectively experimenting within their environment, marking a significant step towards recovery and growth.

Phase 9: Complacency

Complacency is the final stage, where individuals have adapted to the change, rationalized the events, and integrated them into their new worldview.

This stage is characterized by a return to the ‘comfort zone,’ where people feel confident in their ability to handle future events and show a lack of interest in ongoing changes around them. It signifies a full adaptation to the new normal, even if the process is challenging.

Stumbling block 1: Disillusionment

Disillusionment arises when there is a recognition that personal values, beliefs, and goals are not in sync with those of the broader organization or situation. This realization can lead to decreased motivation, focus, and satisfaction, with individuals either withdrawing mentally by doing the minimum required or physically leaving the problem altogether.

It’s a phase where the value difference becomes too significant to ignore, prompting a reevaluation of one’s place within the system.

Stumbling block 2: Hostility

Hostility reflects the continuation of efforts to validate failed social predictions. This stage sees individuals sticking to outdated processes that have repeatedly failed, ignoring new methods, or actively undermining them. It’s a sign of resistance to change and an inability to adapt to new working methods.

Stumbling block 3: Denial

Denial is marked by a refusal to accept change, with individuals acting as though nothing has changed. This stage involves clinging to old practices and ignoring evidence contradicting their beliefs. It’s a defense mechanism where problems are excluded from awareness, embodying the ‘head in the sand’ syndrome.

Stumbling block 4: Anger

Anger is a common emotion experienced during transitions, especially in the early stages. The focus of anger may initially be directed outward but often turns inward over time, leading to feelings of guilt and further depression. This stage reflects frustration with both the situation and oneself for allowing things to spiral out of control.

What does the John Fisher Change Curve mean for change management?

Most change initiatives typically focus on the organizational level, often treating individuals as components within a larger system. This model, however, shifts the perspective by placing the individual at the center of any change process.

Through the lens of the transition curve, it becomes evident that comprehending the effect of change on one’s personal construct systems is crucial.

Individuals need to navigate the consequences of their self-perception. Regardless of size, changes can affect individuals by creating conflicts between existing values and beliefs and newly anticipated ones.

Additionally, this model highlights that to facilitate effective navigation through transitions, one must grasp an individual’s perception of their past, present, and future. Questions such as their previous experiences with change, how these experiences affected them, and how they managed are pertinent.

Understanding what they stand to lose and gain from the change is vital. Risks arise when individuals continue to employ practices that have previously led to failure or undesirable outcomes, failing to adapt and expand their worldview.

Another risk is denial, where individuals refuse to acknowledge change, persisting in their usual ways. Both scenarios can adversely affect an organization’s efforts to modify its culture and focus.

Tips to help with the implementation of the John Fisher Change Curve within your business

Understanding the stages of the Change Curve enables you to strategize effectively to reduce the adverse effects of change and facilitate quicker adaptation.

Below is a structured approach to effectively apply this model:

Address the initial shock and confusion through communication

In the face of significant change, employees often experience confusion or surprise.

For change to be embraced, employees must grasp the urgency and necessity behind it. A clear, compelling explanation of why the change is happening and why now is the right time is crucial for motivating staff to invest their efforts.

Without this understanding, employee engagement and commitment to the change process are unlikely, as employees might not see the value in adapting.

Hosting a meeting to address all team members collectively allows for an open forum where questions can be answered, and the change can be contextualized, fostering a connection to the new direction. It’s crucial to share information measuredly to avoid overwhelming employees.

Regular, clear communication is essential but should be balanced to ensure information is digestible. Providing a go-to resource for additional inquiries and making oneself available for follow-up questions can help ease the transition.

Engage and support employees continually during the change

Managers should actively engage with their teams to understand individual concerns and values.

Regular check-ins, whether in coaching sessions or team meetings, to celebrate successes and discuss improvements can create a culture of continuous feedback and personal investment.

This approach also encourages employees to self-reflect and consider how they can contribute to enhancements. By listening and responding to employees’ ideas, managers can co-create solutions that make the change management process more effective and inclusive.

Leverage a coach for leaders

Leaders spearheading change initiatives can benefit from coaching to refine their approach to managing others and optimizing their strengths.

A coach offers support and a listening ear, posing challenging questions that provoke deep thinking and personal growth.

This partnership can bolster a leader’s confidence in their path and strategies, ensuring they are well-equipped to navigate the complexities of change management.

Prepare for and manage negative reactions

Anticipating negative reactions, such as anger or resentment, allows managers to approach these responses constructively rather than with frustration.

Recognizing the wide range of emotions change can provoke and providing the necessary support helps employees move beyond initial resistance.

Preparing employees through training and early exposure to the changes can facilitate learning and acceptance, acknowledging that employee productivity may dip during this adjustment phase.

Reflect on and learn from the change

After navigating through the change, evaluating its outcomes and preparing for future transitions is beneficial. This reflection can be particularly enlightening for employees experiencing their first significant change, reinforcing the certainty and commitment to managing it positively.

Soliciting feedback through surveys or conversations can highlight areas for improvement, enabling a more effective approach to future changes. Acknowledging the learning opportunities each change presents allows for continual adaptation and growth.

Next steps for the John Fisher Change Curve

The John Fisher Change curve highlights the importance of understanding the impact of change on one’s personal construct systems and self-perception. Recognizing how change affects individual values and beliefs is crucial for navigating through transitions effectively.

Facilitating a smooth transition involves understanding individuals’ perceptions of their past, present, and future experiences with change, including their coping mechanisms and what they stand to lose or gain.

The role of managers or a change agent is to make this transition as seamless as possible by providing support, education, and information, helping individuals to adapt and emerge successfully from the process.

The emotional response to change can lead to challenges, including failure to recognize signs of stress or adopting ineffective coping strategies. Individuals typically progress through all stages of transition, albeit at different speeds, with each phase building upon the lessons learned from the previous ones.

Experiencing multiple transitions simultaneously can compound the impact on an individual’s self-confidence and self-image, making it harder to navigate the changes effectively.

Personal transformations are gradual, with the realization of change happening subtly over time. The speed at which individuals transition depends on their self-perception, past experiences, and sense of control over the outcome. A positive outlook and perceived control over the process can ease the transition journey.