Situational leadership theory could be the missing element in your leadership vision for the challenges of the coming decade.

A leading McKinsey report from 2023 highlights why. The successful enterprises of the future will require adaptable management teams to become “open, collaborative, and emergent” businesses. In McKinsey’s terms, this is the exciting trend of the “thriving organization.”

Unlike rigid models, situational leadership provides insights that tools like agile project management often miss. It allows leaders to assess staff motivation, adjust their leadership style accordingly, and guide teams toward goals with high levels of satisfaction. This adaptability also makes situational leadership an important approach for effective change management, ensuring leaders can respond to shifting circumstances with confidence.

In this article, we’ll define situational leadership theory, outline its four core behavior types, explain how it connects motivation with “performance readiness,” and examine its major benefits and challenges.

What is situational leadership theory?

Situational leadership theory examines the interactions between people, motivation, and leadership choices. It suggests no single “correct” way to give instructions and encourage staff. Rather, managers must effectively handle their interactions with staff to achieve positive organizational outcomes.

This makes organizations seem complicated. As anyone knows, staff can change their motivation levels from one task to the next, and leaders must learn how to respond appropriately.

SLT takes another step by showing how to understand staff motivation and how to respond to it. The pioneers of the theory, Paul Hersey and Ken Blanchard, showed how the “performance readiness” of staff should connect with the “behavior style” of leaders. One of the most famous symbols of situational leadership theory is the “wishbone”-shaped graph, which visually connects these two factors.

In its time, situational leadership solved a specific problem. Many writers suggested that management was a “universal” science. They thought that we would find a basic template for all organizational behavior (if we just did enough work).

In their book Management of Organizational Behavior (1969), Hersey and Blanchard showed that reality is much more complicated. Many leaders today recognize this. However, the lessons of situational leadership are still a provocative and exciting approach.

After all, it is common to see people arguing for a widespread idea of HR best practices, most notably in Jeffrey Pfeffer’s work. Situational leadership provides a thorough model for context-specific responses to problems and issues.

Like any leadership practice, situational leadership is not perfect. Scholars like Geir Thompson have carefully evaluated the ideas of situational leadership (see their articles in 2009 and 2018). Like any leadership theory, this is a set of ideas that adapt and change over time.

The four behavior styles of situational leadership

Situational Leadership Theory introduces four distinct behavior styles that leaders can employ depending on the readiness level of their team members. These styles are:

- Telling

- Selling

- Participating

- Delegating

These behavior styles balance two important aspects: task behavior and relationship behavior. Task behavior involves giving instructions and guiding the team on what needs to be done. Relationship behavior focuses on building connections and motivation within the team.

In the rest of this section, we will introduce the four major behavior styles in situational leadership.

- Telling, directing, or guiding

In this style, the leader provides specific instructions and closely supervises task completion. This style is most appropriate when followers have low readiness levels and need clear guidance and direction. With “telling,” leaders prioritize task behavior.

Example: A new employee is hired in a manufacturing plant. The supervisor provides detailed instructions on operating a specific machine and closely monitors the employee’s performance during the initial training period.

- Selling, coaching, or explaining

Here, the leader provides both direction and support. They explain decisions, gather input, and encourage questions. This style is effective when followers have moderate readiness levels but still need guidance.

Example: A project manager is leading a team of software developers to create a new application. The manager explains the project’s goals, provides guidance on the development process, and motivates team members by highlighting the importance of their contributions.

- Participating, facilitating, or collaborating

This style involves more delegation and support from the leader. In other words, it prioritizes relationship behavior over task behavior.

Leaders encourage followers to take initiative and make decisions while providing resources and assistance as needed. This style suits followers with moderate to high readiness levels who may benefit from increased autonomy and empowerment.

Example: A department manager encourages her team members to take ownership of their tasks and make decisions regarding project implementation. She offers resources and assistance as needed but trusts her team to manage their responsibilities autonomously.

- Delegating, empowering, or monitoring

In this style, the leader provides minimal direction and support. They allow their followers to take full responsibility for task completion. The leader still monitors progress but grants followers a high degree of autonomy. This style is most appropriate for followers with high readiness levels who can work independently.

This style is low in both task and relationship behavior. It’s appropriate when there’s a high level of trust and understanding between a leader and their team.

Example: A business owner delegates the responsibility of managing day-to-day operations to the store manager. The owner provides general guidelines and expectations but allows the manager to make staffing, inventory management, and customer service decisions without constant oversight.

What are the different types of performance readiness in situational leadership theory?

In Situational Leadership Theory, leadership behaviors align with performance readiness.

Performance readiness is a measure of motivation that gauges how far staff members are prepared to tackle tasks.

These readiness levels, termed “maturity levels” in earlier versions of the theory, include:

- Unable and unwilling

- Unable but willing

- Able but unwilling

- Able and willing.

In this section, we will explain the meaning of each one in turn.

Unable and unwilling

At this level, individuals lack the necessary skills or confidence to perform a task and may be unwilling to take on the responsibility.

Example: A new team member joins a marketing project requiring advanced data analysis skills. However, they lack experience with data analysis software and feel overwhelmed by the task’s complexity, leading to reluctance to take it on.

Unable but willing

At this level, individuals are motivated and willing to perform the task but lack the necessary skills or knowledge. They may need guidance, training, or support to complete the task successfully.

Example: A software developer volunteers to lead a new project using a programming language they’re unfamiliar with. Despite their enthusiasm, they require support and mentoring from senior team members to grasp the language and meet project requirements.

Able but unwilling

Here, individuals have the skills and knowledge required to perform the task but lack the motivation or confidence to do so. They may need encouragement, reassurance, or incentives to take responsibility.

Example: An experienced sales representative is hesitant to take on a leadership role in a client presentation despite having the necessary expertise. They require reassurance and support from their manager to overcome self-doubt and step into the leadership role.

Able and willing

This is the ideal level of performance readiness, where individuals have both the skills and the motivation to perform the task effectively. They are confident and willing to take on responsibility independently.

Example: A seasoned project manager confidently leads a cross-functional team through a complex project, leveraging their expertise and motivation to guide team members toward successful completion.

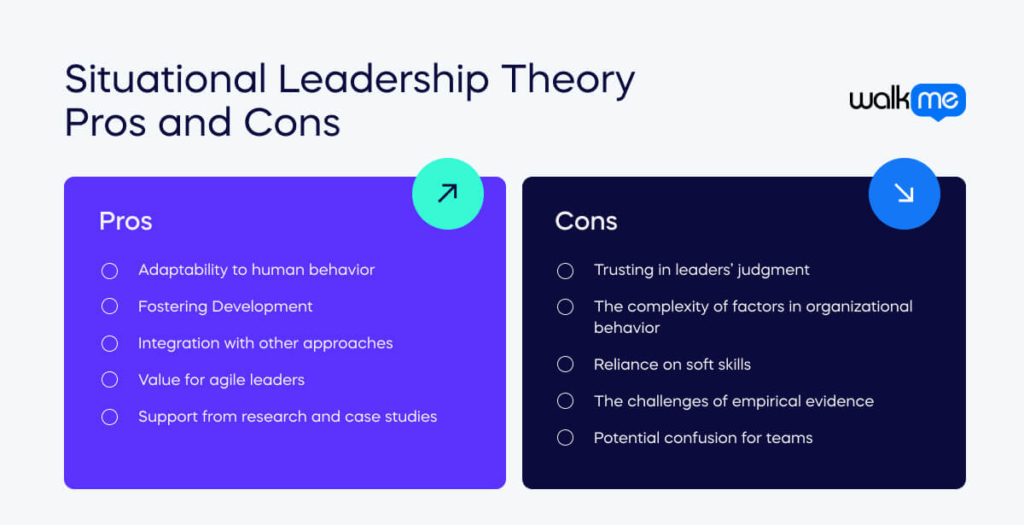

What are the benefits of situational leadership theory?

Situational Leadership Theory has been around for nearly six decades. Yet, it is still vitally important for many leaders. SLT has many distinct benefits that make it very different from other approaches, so it is no surprise that business people keep coming back. The benefits include the following.

Adaptability to human behavior

SLT recognizes the ever-changing nature of human behavior. It helps leaders to respond without relying on rigid responses or cookie-cutter thinking. It can adapt to many situations.

Fostering Development

By emphasizing flexibility and responsiveness, the theory promotes a culture of learning. SLT encourages continuous staff training under the guidance of adaptable leadership.

Integration with other approaches

Situational Leadership works well with other leadership methodologies. For instance, its participatory behavior style aligns well with servant leadership principles. It also goes well with empathetic leadership, promoting understanding and support within teams.

Value for agile leaders

Agile methods benefit significantly from Situational Leadership Theory. Agile allows teams to adapt and innovate. SLT adds to this by helping to define a range of managerial responses when they arise. This collaboration with agile team leadership fosters a dynamic and responsive work environment.

Support from research and case studies

Backed by extensive research and analysis, Situational Leadership Theory offers an academically robust framework supported by a wealth of case studies and examples. This ensures its applicability and effectiveness in addressing real-world challenges.

What are the challenges of situational leadership theory?

As we’ve seen in this article, situational leadership has a lot of positive benefits. However, it is not perfect. Some of the major problems with situational leadership include the following points.

Trusting in leaders’ judgment

SLT places significant emphasis on leaders’ judgment when assessing follower readiness levels. However, this skill may be challenging for many leaders to develop. Accurately gauging readiness requires experience, intuition, and insight, which may not come naturally to all leaders.

The complexity of factors in organizational behavior

Much about SLT “rings true” – it seems like common sense! However, in difficult times, mastering SLT is no small feat. It involves navigating a dynamic landscape of situational factors, individual motivations, and leadership behaviors.

Reliance on soft skills

SLT assumes a foundation of soft skills, such as communication, empathy, and emotional intelligence, essential for effective leadership. However, not all leaders possess these skills innately. Incorporating SLT into leadership training programs alongside other soft skills development initiatives can address this challenge.

The challenges of empirical evidence

Producing clear-cut empirical evidence to validate SLT can be challenging. As a result, SLT may be better suited as a subjective approach rather than relying solely on empirical evidence.

Potential confusion for teams

Constantly shifting leadership behaviors based on situational factors may confuse teams and undermine stability. Teams may struggle to understand and adapt to rapidly changing leadership styles, leading to uncertainty and inefficiency.

Navigating these challenges requires leaders to approach SLTs with humility, adaptability, and a commitment to development.

Why situational leadership is so effective

Today, Business leaders know they need emotional intelligence (EQ) to match their academic intelligence (IQ). SLT opens doors for a generation of leaders who wear their soft skills on their sleeves.

The theory can challenge the status quo by addressing the lack of diversity in leadership teams.

The possibilities of SLT remind us just how far we’ve come from the theories of “scientific management” in the first part of the twentieth century. Businesses, organizations, and people have all changed beyond recognition, and SLT is one of many postmodern leadership theories that address these challenges.