Adopting a systems or systemic change enables leaders to comprehensively assess the organization’s dynamics, which supports crafting effective change management solutions and their implementation.

Systemic change is imperative as many organizational issues are deeply embedded in existing systems, structures, and foundational beliefs.

This process demands a deep overhaul of the organization’s core aspects, including culture, procedures, policies, and leadership vision.

Nonetheless, systemic change often seems daunting to businesses due to its complexity. Additionally, the lure of immediate results and financial objectives can sidetrack the focus from systemic change, tempting organizations to postpone these essential shifts for future consideration.

To help you understand the value of systems change, this article will describe a system change, its purpose, and its various components. You will also learn about implementing systemic change, with examples, and the pros and cons of systems change.

What is systems change?

Systems change, or systemic change involves addressing the fundamental causes of problems rather than just their symptoms. This transforms the underlying structures, customs, mindsets, power dynamics, and policies.

It emphasizes enhancing the collective strength of an organization through the cooperation of diverse individuals and organizations united by common objectives. This approach aims for enduring solutions to social issues locally, nationally, and globally.

The systems change process can begin with incremental changes that enhance performance within the current framework and norms. It then progresses to structural changes, leading ultimately to profound, transformational changes that introduce innovative solutions and new approaches to problem-solving.

What is the purpose of systems change?

Companies can embrace systems change to alter the status quo through collective action by individuals, organizations, and policymakers involved in an issue, ensuring that old patterns are not reverted.

Moreover, systems change magnifies the impact beyond what individual efforts can achieve. This is because it can facilitate broad, significant transformations that can revolutionize an entire organization. It fosters more resilient communities and better prepares them for future adversities.

Additionally, systems change speeds up innovation, paving the way for new technologies, business models, and social frameworks that stimulate economic development.

What are the components of systems change?

Exploring the components of systems change offers businesses a comprehensive understanding of the essential elements required to enact meaningful transformations within their operational frameworks, fostering adaptability and innovation for long-term success.

Meaningful and sustainable change within systems hinges on several key elements:

Leadership

Effective change leadership plays a pivotal role in rallying and influencing individuals. For systems change to be effective, it requires leaders who are experienced, realistic, and adept in collaboration, capable of inspiring progress and embodying the vision.

Leadership should permeate all levels of an organization since no single leader possesses all the necessary knowledge and skills for comprehensive systems change. Leaders must balance practical operational abilities with visionary insight, converting ambitious goals into tangible outcomes. The focus should be nurturing leaders committed to fostering positive transformations through individual and collective efforts.

Background

Understanding the history behind change is crucial for cultural and systemic shifts. The presumption that employees will readily embrace change overlooks the skepticism bred from witnessing repeated, unsuccessful reform attempts. Recognizing this historical context within an organization is vital; it informs the approach to engaging employees who may adopt a ‘wait and see’ stance toward new initiatives.

Contextual awareness

Understanding and being on top of the world around you is essential. The global landscape influences perceptions of current events and affects receptiveness to change. Understanding what is seen as possible, desirable, urgent, or opportune reflects the importance of context. It shapes the strategies for identifying and leveraging moments ripe for systems change.

Inclusive stakeholder engagement

Stakeholder alliances or a cross-functional team will simplify consensus-building and vision development, which is critical for melding diverse perspectives into unified coalitions. Such partnerships are instrumental in marshaling collective action, energy, and intent.

Stakeholder forums play a crucial role in crafting compelling responses to challenges posed by systems change, allowing for the refinement of ideas through broad participation. This inclusivity ensures that solutions address the concerns of many rather than a select few.

These are formed by identifying relevant parties and determining what attracts and retains their engagement. While these alliances are vital in launching new change initiatives, it’s essential to recognize that impactful change doesn’t have to be monumental from the outset. Even small-scale projects can significantly challenge and alter entrenched norms and practices.

How to implement systems change

Systems change is fundamentally about uniting all stakeholders to drive a societal-level business transformation. It involves empowering visionaries, persuading those invested in the status quo to shift, and enhancing cooperation among frontline workers for greater efficacy and efficiency. This collaborative effort aims to address complex challenges through collective action.

However, implementing systems change is fraught with complexities. Organizations often face confusion about the need for change, resistance from staff, and leadership challenges in aligning team efforts.

Addressing these issues requires strategic approaches and best practices to ensure successful systems change:

Understanding existing systems

The imperative to deeply understand existing systems is at the heart of systems change. This means going beyond surface-level symptoms to grasp the underlying causes and dynamics perpetuating problems. It involves a comprehensive analysis of stakeholders, their interrelations, and the external factors influencing the system.

This foundational step ensures that change efforts are targeted and practical and avoids unintended consequences that could exacerbate existing issues or create new ones. Understanding the system’s architecture—its incentives, power structures, and prevailing narratives—is crucial for crafting interventions that can genuinely shift the status quo.

Appreciate that problems are connected

A systemic view is instrumental in recognizing the interconnectedness of challenges and the ripple effects that changes in one part of a system can have on others. This perspective requires a thoughtful consideration of trade-offs, the potential for unintended consequences, and the complex web of cause-and-effect relationships that define systems.

A change management agent can anticipate and mitigate negative impacts by adopting a systemic view, ensuring that solutions contribute to holistic and sustainable improvements. Systems mapping emerges as a powerful tool in this context, offering a visual and analytical method to understand and navigate the complexities of systems change.

Plan for the systems change

Preparation is vital to the successful implementation of systems change. This preparation involves open discussions about anticipated changes, ensuring that all organizational levels are informed and equipped to adapt to new workflows.

The human aspect of change is particularly significant; engaging with and understanding the concerns and aspirations of those affected by the change is vital for fostering an inclusive, supportive environment. This stage also involves strategic planning to address power dynamics, biases, and resource allocation to ensure equitable change.

Understand your role in the change

Systems change is a collective endeavor that requires each participant to understand and embrace their unique role within the broader ecosystem.

This understanding is not just about acknowledging one’s responsibilities but also about proactively seeking feedback, engaging in meaningful relationships with other system actors, and finding one’s niche where strategic contributions can be made. Reflecting on our roles allows for a more nuanced engagement with the system, enabling targeted and impactful actions.

Ensure it includes clear communication and training

Effective communication and comprehensive employee training are indispensable components of systems change. Articulating the vision, rationale, and expected outcomes of the change process helps to align and motivate all stakeholders.

Training programs tailored to specific roles and departments ensure everyone has the knowledge and skills to navigate the new system. Identifying and empowering ‘super users’ or change agents within the organization can facilitate a smoother transition, acting as champions for change and supporting their colleagues through challenges.

Encourage continual feedback and improvement.

Feedback mechanisms are critical throughout the system’s change process. They provide valuable insights into the change’s effectiveness, areas for improvement, and overall impact on the organization and its stakeholders.

This employee feedback loop, coupled with a commitment to continuous training and adaptation, helps to sustain momentum and ensure that the systems change process remains relevant and responsive to emerging challenges and opportunities.

Practical examples of systems change

Mastering the implementation of systemic changes within your organization also requires a deep comprehension of the role that companies, in particular, can play in effecting transformation within complex systems.

Here are some illustrative examples to guide you toward successful execution:

Petey Greene Program

Founded in 2008 at Princeton University, the Petey Greene Program emerged to recruit college students and community volunteers to provide tutoring services to incarcerated individuals.

From its inception, the program made a significant impact at the individual level, addressing the educational needs of many incarcerated individuals who lacked a high school diploma, a symptom of the US’s school-to-prison pipeline.

These individuals could achieve academic success through personalized support, which fostered their self-confidence, especially seeing volunteers consistently return to support them.

For the volunteers, this interaction with incarcerated students prompted a deep reflection on the injustices of the criminal legal system, its ties to educational inequality, and their positions within these structures. The program demonstrated a mutual benefit, altering perceptions of self and others and challenging the notions of oppression and dominance.

By the time Alison Badgett assumed the role of executive director, the Petey Greene Program had expanded significantly, recruiting over 1,000 volunteers annually from 30 universities to tutor 2,500 incarcerated students each year across 50 jails and prisons in seven Eastern states and the District of Columbia.

But, while the program encouraged its volunteers to become advocates, the organization maintained a neutral stance on policy issues. This position risked portraying it as complicit in perpetuating an unjust system by addressing its symptoms rather than its root causes. This stance was rooted in concerns among the staff and board that engaging in systemic change efforts might dilute the program’s focus.

Badgett aimed to guide the organization through a strategic planning process that embraced systems change from a social justice perspective. She believed that properly implemented, a systems change model would not scatter the program’s efforts but rather sharpen its focus, enhancing and expanding its educational services, underpinned by heightened public awareness and policy engagement.

The critical role of access to quality education in supporting decarceration was evident, necessitating a shift from merely coordinating volunteer efforts to actively training and mentoring high-quality tutors.

This shift required developing new skills among the staff and reallocating resources to create positions dedicated to operations, curriculum development, training, evaluation, and communications.

The systems change model advocated piloting innovative educational models and promoting them as policy. It demanded more from correctional facilities, including consistent access to academic resources and funding to sustain and enhance programming quality.

Furthermore, the program was responsible for its participants’ educational outcomes beyond their incarceration, continuing support post-release, and exploring preventative measures against imprisonment, such as intensive educational interventions as alternatives to sentencing for youth.

This comprehensive approach marked a significant evolution in the Petey Greene Program’s strategy, aiming to address both the immediate educational needs of incarcerated individuals and the systemic issues contributing to mass incarceration.

Safety-net institutions and New Mexico

Safety-net institutions (SNIs), which serve low-income and at-risk populations, face significant challenges due to their reliance on public funding, making them vulnerable to systemic changes.

High turnover rates, exacerbated by the pressures of maintaining provider retention and adapting to new administrative demands, jeopardize their operational effectiveness and the continuity of care.

In 2005, New Mexico’s shift to managing all publicly funded behavioral health services under a single for-profit entity introduced a managed systems change care approach. This approach focused on efficiency and quality while increasing administrative burdens and financial strain for SNIs.

Many struggled with the new billing and reimbursement requirements amid technological and support deficiencies.

A National Institute of Mental Health-funded study assessed the impact on SNIs in this area, including a variety of mental health and substance abuse treatment centers. It found that 22% of participants experienced voluntary turnover within 1.5 years of assessment. Half of the 14 SNIs studied reported high stress due to the reform.

The research highlighted that positive leadership within SNIs under stress could mitigate the adverse effects on organizational development and turnover. Findings indicated that a positive organizational climate was linked to lower turnover intentions, underscoring the critical role of retaining trained staff to ensure effective client and coworker relationships and adapt to new service delivery models under the reform.

While not all staff turnover is detrimental, fostering a supportive work environment through effective leadership and a positive climate is essential for minimizing voluntary turnover, facilitating organizational change, and adopting evidence-based practices.

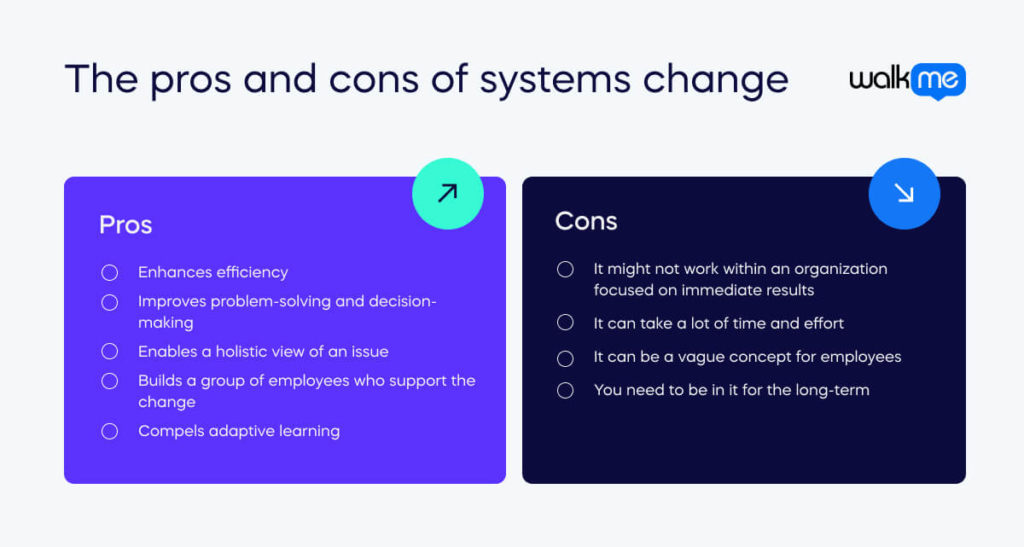

The pros and cons of systems change

Adopting a systemic change approach offers numerous advantages in addressing enduring challenges related to people and performance during transformational change efforts.

These are:

Enhances efficiency

Systems change introduces novel methodologies to boost efficiency and maximize available resources. By delving into an organization’s structure and the interplay between its components, systems change opens avenues for fresh ideas and innovations.

This process is instrumental in quickly pinpointing problems and experimenting with solutions, thus enhancing the organization’s capacity to adapt and evolve swiftly. Through this lens, systems change catalyzes continuous performance improvement, allowing businesses to stay ahead in a competitive landscape.

Improves problem-solving and decision-making

Systems change allows you to consider new and improved ways of crafting strategies for solving complex problems. This approach not only aids in problem-solving but also elevates the quality of decision-making.

System change ensures that strategies are impactful and aligned with the organization’s goals by pinpointing leverage points within the system and keeping a firm eye on the desired outcomes and objectives. It transforms the strategic change process, making it more dynamic and responsive to the challenges.

Enables a holistic view of an issue

At the heart of systems change lies the principle of systems thinking, which offers a holistic view of a problem. This perspective compels us to consider a system within its environment and context, striving to grasp the bigger picture.

By embracing the complexity of systems rather than attempting to simplify them, systems thinking enables a deeper understanding of a system’s myriad dimensions and facets. This comprehensive approach is crucial for recognizing the interconnectedness of various elements and the potential impacts of any changes.

Builds a group of employees who support the change

A key goal of systems change is establishing ecosystems of actors who share an understanding of the system, enabling them to collaborate. Developing shared system diagrams and a common language is vital for building everyone’s awareness and fostering collective intelligence.

This process enhances the group’s collective agency and ensures all employees can contribute effectively. Such ecosystems are fundamental for achieving synergy and collaboration across the system, allowing diverse actors to synchronize their activities in ways that amplify their impact.

Compels adaptive learning

To support continuous learning culture and adaptation, systems change emphasizes the importance of building adaptive learning employee feedback loops within the network. These loops facilitate an ongoing exploration of the problem space and potential solutions, encouraging experimentation and learning.

This approach ensures the network remains flexible and responsive to new information and challenges, enhancing its capacity for systemic change. Through adaptive learning, the collective agency of the group is strengthened, making it better equipped to navigate the system’s complexities and effect meaningful change.

However, systems change often has its challenges:

It might not work within an organization focused on immediate results

An existing focus on quick results and immediate action can inadvertently undermine a system-wide mindset, where the urgency and preference for quick wins may lead to overlooking the nuanced, less visible actions that contribute to systemic change. This impatience risks sidelining the comprehensive thinking and actions necessary for genuine systems transformation.

It can take a lot of time and effort

Adopting a systemic approach entails integrating systemic thinking, analysis, and action throughout the change process, considering the dynamics of the more comprehensive system and its effects on your initiatives.

This approach demands dedication to time, space, and energy, which might be perceived as scarce, particularly among frontline staff who often face significant time constraints and limited opportunities for reflection.

Their enthusiasm and optimism are crucial for the successful execution of projects, making it essential to address this challenge head-on in organizational communications and to actively carve out time in their schedules for engaging in systems change activities. Ensuring staff have the time and space for reflection and systemic action is crucial in moving initiatives forward.

It can be a vague concept for employees

For many employees, ‘systems change’ may appear vague and abstract, especially amidst higher-level debates about defining a ‘system’ and the scope of systems change efforts.

Clarifying what systems change entails for individual roles and the organization is crucial for demystifying the concept and fostering a shared understanding. Clear explanations and examples can help employees see how systems thinking applies to their work and the broader organizational goals.

You need to be in it for the long-term

Systems change is often mistakenly viewed as a static destination rather than an ongoing journey. This perspective can lead to a loss of momentum during the implementation phase if employees do not recognize that systems are inherently dynamic, with their components constantly interacting and evolving.

It’s essential to educate employees about the continuous nature of systems change, emphasizing the need for constant sensing, responding, and adapting to changes within the system. Training should focus on preparing employees to engage with systems change as an iterative, responsive process rather than a linear progression toward a fixed endpoint.

Final steps on systems change

In tackling the multifaceted challenges globally, the principle of systems change emerges as a strategy and a critical pathway toward crafting sustainable and impactful solutions. This approach is predicated on a deep, holistic comprehension of the intricate systems that underpin your organization.

It mandates addressing the root causes of issues rather than merely mitigating their symptoms, recognizing that these causes are often deeply embedded in the interconnected fabric of social, economic, and environmental systems. To navigate this complexity, systems change leverages strategic points within these networks, where targeted actions can catalyze widespread enterprise transformation.

However, the journey towards systems change is fraught with challenges. It demands resilience, creativity, and a willingness to experiment and learn from failure. Success in this endeavor is not the result of a monumental effort but rather the cumulative impact of sustained strategic actions.

The collective effort of individuals and organizations, each contributing uniquely, is indispensable. By pooling our resources, knowledge, and energies, we can pave the way for a more resilient future in the face of adversity and sustainability for future generations.

Furthermore, systems change is inherently a dynamic process. It does not conclude with achieving a set goal but continues to evolve in response to new challenges and insights. This necessitates an ongoing commitment to reflection, learning, and adaptation.

Our strategies and interventions must evolve as our understanding of complex systems deepens and the global context shifts. Collaboration remains a cornerstone of this process, enabling sharing insights, pooling resources, and coordinating efforts across different sectors and disciplines.

FAQs

Systems change addresses underlying structures, mindsets, and power dynamics, aiming for long-term transformation. Traditional change management often focuses on specific projects or processes without altering foundational systems.

Effective systems change requires leaders across the organization to collaborate, inspire, and drive transformation. Distributed leadership ensures diverse perspectives and shared ownership of change initiatives.

Without a deep understanding of current systems, interventions may address symptoms rather than root causes, leading to ineffective or unsustainable changes.

Enterprises should consider systems change when facing persistent challenges that resist conventional solutions, indicating the need for fundamental shifts in structures and processes.

Systems change provides a holistic framework that aligns organizational culture, policies, and structures, facilitating the adoption and integration of digital technologies.